alias: AL WILSON, JAKE SONDHEIM, JEW AL

SNEAK, PICKPOCKET, FORGER, CONFIDENCE MAN

Everard FeildingThe following tale comes to us courtesy of barrister/psychic researcher (not a combo one sees every day) Everard Feilding, in the form of two letters he sent his friend Hereward Carrington, who published them in the 1951 book “Haunted People.” It is a rather delightful poltergeist account, complete with a supernatural snipe hunt!Transylvania,Jan. 26, 1914Dear Carrington,Your

More...

Strange Company - 4/21/2025

Included in yesterday’s trip to Fall River was a stop at Miss Lizzie’s Coffee shop and a visit to the cellar to see the scene of the tragic demise of the second Mrs. Lawdwick Borden and two of the three little children in 1848. I have been writing about this sad tale since 2010 and had made a previous trip to the cellar some years ago but was unable to get to the spot where the incident occured to get a clear photograph. The tale of Eliza Borden is a very sad, but not uncommon story of post partum depression with a heartrending end. You feel this as you stand in the dark space behind the chimney where Eliza ended her life with a straight razor after dropping 6 month old Holder and his 3 year old sister Eliza Ann into the cellar cistern. Over the years I have found other similar cases, often involving wells and cisterns, and drownings of children followed by suicides of the mothers. These photos show the chimney, cistern pipe, back wall, dirt and brick floor, original floorboards forming the cellar ceiling and what appears to be an original door. To be in the place where this happened is a sobering experience. My thanks to Joe Pereira for allowing us to see and record the place where this sad occurrence unfolded in 1848. R.I.P. Holder, Eliza and Eliza Ann Borden. Visit our Articles section above for more on this story. The coffee shop has won its suit to retain its name and has plans to expand into the shop next door and extend its menu in the near future.

More...

Lizzie Borden: Warps and Wefts - 2/12/2024

In the middle decades of the 20th century, Maurice Kish was probably not unlike many of his South Williamsburg neighbors. “Poultry Market,” 1940 Born in Russia in 1895, he immigrated to New York as a teenager, settling in Brownsville with his family. He served in the military and left it in 1919. Like so many […]

More...

Ephemeral New York - 4/21/2025

Youth With Executioner by Nuremberg native Albrecht Dürer … although it’s dated to 1493, which was during a period of several years when Dürer worked abroad. November 13 [1617]. Burnt alive here a miller of Manberna, who however was lately … Continue reading

More...

Executed Today - 11/13/2020

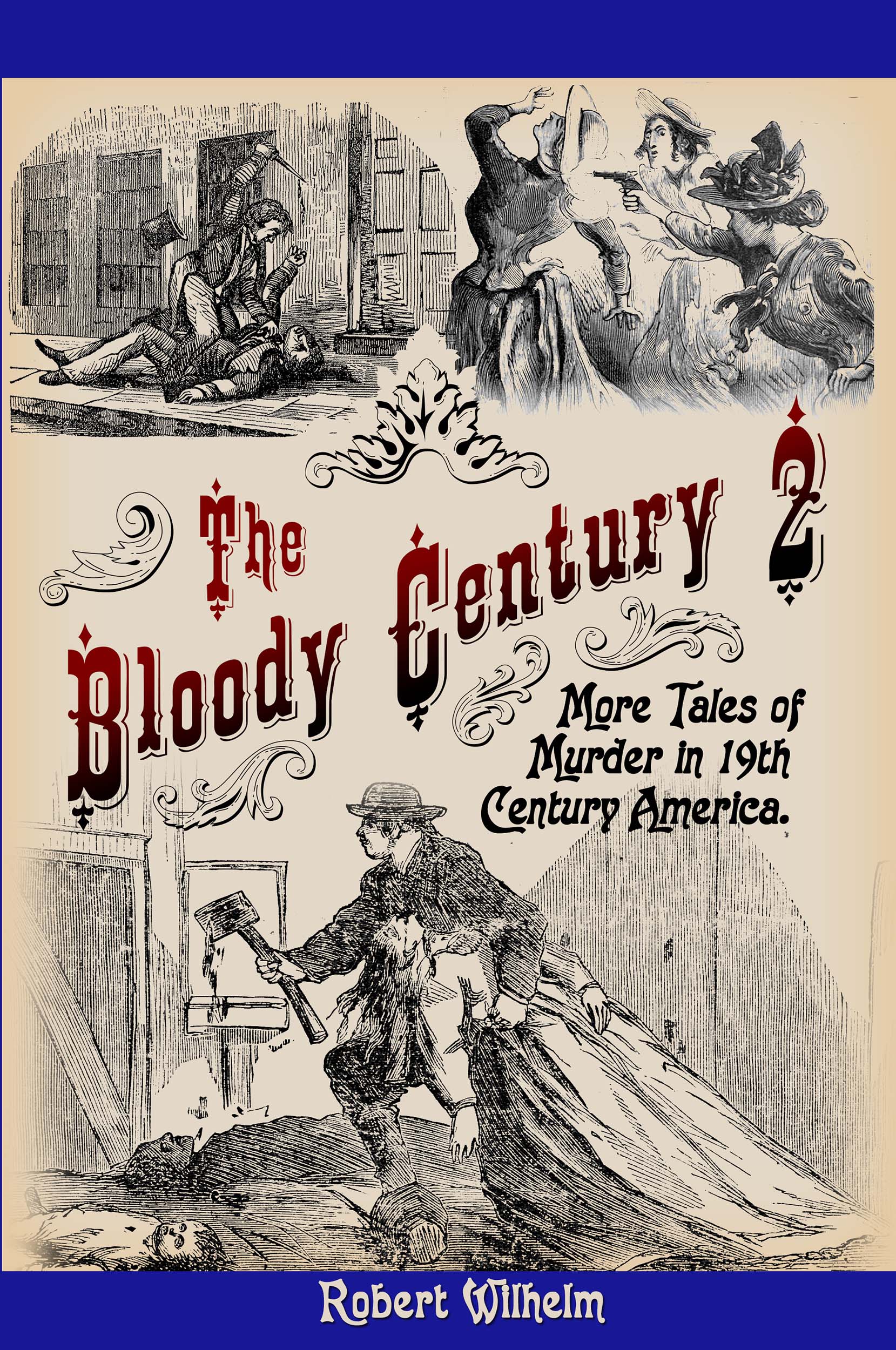

As Police Officers Henry Johnson and Eli Veazie were leaving

the Chelsea, Massachusetts City Marshal’s office on the evening of February 17,

1872, they were approached by a man, intoxicated and in a state of agitation.

“I have had my revenge. I want you to go with me,” he said, “I

suppose I have killed him and shall have to suffer for it.”

The man, Arzo B. Bartholomew, led them to a men’s

More...

Murder By Gaslight - 4/19/2025

Soapy Smith STAR NotebookPage 19 - Original copy1884Courtesy of Geri Murphy(Click image to enlarge)

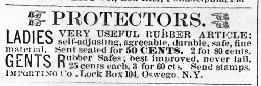

oapy Smith begins an empire in Denver.Operating the prize package soap sell racket in 1884.This is page 19, the continuation of page 18, and dated April 14 - May 5, 1884, the continuation of deciphering Soapy Smith's "star" notebook from the Geri Murphy's collection. A complete introduction to

More...

Soapy Smith's Soap Box - 4/3/2025

[Editor’s note: Guest writer, Peter Dickson, lives in West Sussex, England and has been working with microfilm copies of The Duncan Campbell Papers from the State Library of NSW, Sydney, Australia. The following are some of his analyses of what he has discovered from reading these papers. Dickson has contributed many transcriptions to the Jamaica […]

More...

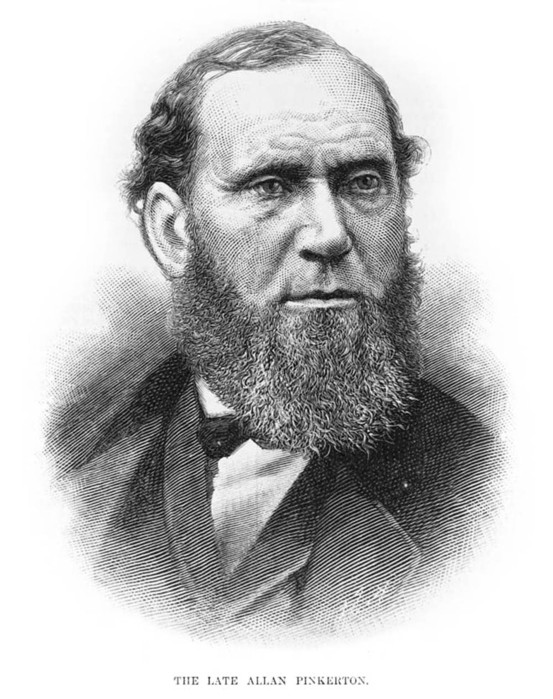

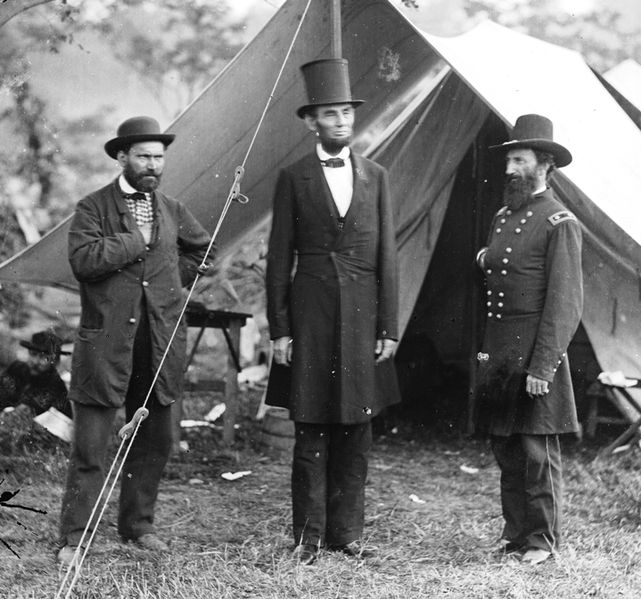

Allen Pinkerton, Pres. Lincoln, Maj. Gen. McClernand

Allen Pinkerton, Pres. Lincoln, Maj. Gen. McClernand