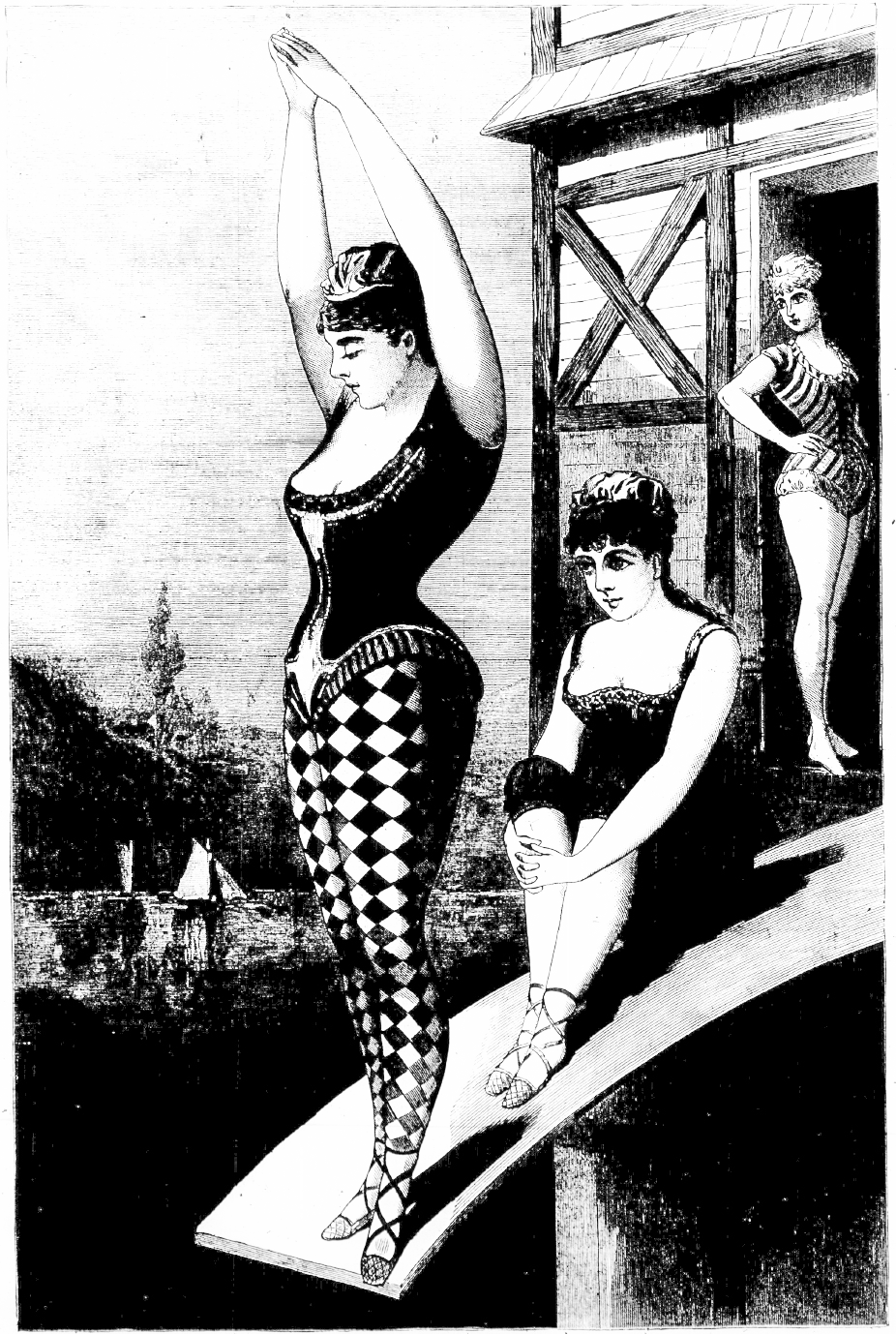

The Last Dip of the Season.

Water witches who frolic with Neptune, no matter how cold his embrace.

September 10, 2019

alias: ENGLISH FRANK HILTON, PADDY, PICKPOCKET

Via Newspapers.com…Well, perhaps not the worst, but certainly something you wouldn’t want in the neighborhood. The “Rutland Daily Herald,” September 7, 1874:From New Martinsville. West Virginia, comes the latest ghost story. If we may credit the account given by the Wheeling Intelligencer, there lives, 25 miles up Fishing Creek, and about 20 miles from Burton, one Henry Nolan, A wealthy and

More...

Strange Company - 1/28/2026

"As his son I am proud of hisefforts to succeed in life"Jefferson Randolph Smith IIIArtifact #93-2Jeff Smith collection(Click image to enlarge)

oapy's son hires a legal firm to stop the defamation of his father's name.

At age 30, Jefferson Randolph Smith III, Soapy and Mary's oldest son, was protecting his father's legacy and his mother's reputation from "libel" and scandal. He was also

More...

Soapy Smith's Soap Box - 10/13/2025

A fashionable townhouse in 19th century Brooklyn would have had many stylish features—like a tall front stoop, iron railings on the stairs, and a ground-level side door through which servants could come and go unseen. A townhouse like this would also have a coal hole. You’ve probably seen these in many older residential areas of […]

More...

Ephemeral New York - 1/26/2026

Youth With Executioner by Nuremberg native Albrecht Dürer … although it’s dated to 1493, which was during a period of several years when Dürer worked abroad. November 13 [1617]. Burnt alive here a miller of Manberna, who however was lately … Continue reading

More...

Executed Today - 11/13/2020

James E. Eldredge and Sarah Jane Gould.(The Trial of James E Eldredge )James E. Eldredge left his home in Canton, New York in the spring of 1856. He returned six months later with a new name and a duplicitous personality to match. All those around him soon learned to distrust anything the young man said—all except his fiancé, Sarah Jane Gould. She remained trusting to the end, when

More...

Murder By Gaslight - 1/24/2026

The good-looking thirty-seven year old gentleman handling the reins behind the glossy matched pair pulling the spanking-new carriage drew the attention of more than one feminine eye. Pacing down French St. at a sharp clip, the lady next to him, dressed neatly in a tailor-made suit with the latest in millinery fashion, smiled up at her coachman. Behind the lace curtains on the Hill section of Fall River, tongues were wagging about the unseemly pair. Lizzie Borden, acquitted of double homicide just six years earlier had come into her money and also her style of spending it on the good things in life. Just what was going on between Lizzie and that coachman, unchaperoned and traveling together all around town? Chief among those who disapproved of the new coachman was sister Emma, who had been perfectly satisfied with Mr. Johnson, the former coachman who had managed their father’s Swansea farm. This new addition to the house on French St. was far too “at home” and casual for Emma’s proper standards. He did not behave sufficiently as a servant who ought to know his place. His presence in their home was causing gossip and attention, a deplorable situation for the retiring, modest older sister. Handsome Joe would have to go and Emma made sure of that in 1902 after three years of Joe’s service to the Borden sisters. Lizzie was not well-pleased with the dismissal. Ever since Emma Borden packed her bags and left French St. for good in 1905, friends, neighbors and now historians wonder what caused the split between two sisters who had been so close all their lives. Much has been made of the passing and short friendship Lizzie formed with actress Nance O’Neil as a possible cause of the rift, as well as “theater people” in the house and strong drink. Most likely it was a combination of things but one thing was for sure- Emma’s dismissal of the good-looking young coachman whom Lizzie had hired to drive her around town was a factor. 1900 census listing Joe, Annie Smith (housekeeper) Lizzie and Emma So, where did he come from and what became of Joseph Tetrault (also Tetreau and Tatro)? Born on February 9, 1863 in Kingston, R.I. of French Canadian parents, he worked as a hairdresser/barber on Second Street in Fall River at one time. Later we find him living a short distance away on Spring Street at a boarding house owned by Lizzie and Emma after the murders in 1892. His parents, Pierre Tetreau dit Ducharme and his mother,Almeda Fanion were from Rouville, Quebec and had moved to Kingston, Rhode Island. Pierre worked in a woolen mill and had nine children with his first wife, Marie Denicourt, and six more with second wife, Almeda. The last six included : Edward Peter 1861-1940 Joseph H. 1863-1929 Mary Elizabeth “Mamie” 1865-1956 Frederick A. 1871-1947 Francis “Frank” 1875-1935 Julia E. 1877-1973 We can only imagine the conversation between Lizzie and Emma about Joe Tatro – the arguments put forward, even heated discussions, but in the end, Lizzie had her way and in 1904 rehired Joe to resume his duties on French Street. Added to Emma’s unhappiness about Nance O’Neil and other factors, Emma and Lizzie parted company in 1905. Joe remained driving Miss Lizzie until 1908, and for whatever reason, decided to move on. The 1908 directory lists him as “removed to Providence”. Joe never married. Perhaps he remembered his childhood in a house full of siblings and half siblings and parenthood never appealed to him. He decided to try his luck out in Ohio where his youngest sibling, Julia, had gone, now married to Alfred Lynch and where eventually all his full siblings would find their way. Al Lynch worked as a supervisor in a machine works in East Cleveland and he and Julia had two sons, Alfred Jr. and an oddly -named boy, Kenneth Borden Lynch. One has to wonder about this last name. Lizzie had two beloved horses, Kenneth and Malcolm. Was this a connection to Joe’s happy past on French Street where he had driven that team of horses? Lizzie presented Joe with a handsome heavy gold watch chain when he left her in 1908. The watch fob had an onyx intaglio inset of a proud horsehead to remind him of their days on French St. Joe’s youngest sibling Julia, who married Al Lynch. She was the mother of two sons including Kenneth Borden Lynch Sadly, Kenneth Borden Lynch was to marry, produce one son, and one day while attending to his motor vehicle, was run over by a passing Greyhound bus. Kenneth Borden Lynch, Joe’s nephew Joe Tatro developed cancer of the stomach and died at the age of 66 ½ from a sudden stomach hemorrhage on August 10, 1929. His last occupation was one of a restaurant chef. He was a long way from those carefree Fall River days. He was buried in Knollwood Cemetery on August 12th from S.H. Johnson’s funeral home. His last address at 1872 Brightwood St. in East Cleveland is today just a vacant lot in a tired old residential neighborhood. He shared the home with another married sister, Mary R. Tatro Asselin. There are still a few direct descendants of his immediate family alive, and they are aware of his connection to Lizzie Borden. Whatever memories of her, Joe took with him to the grave. (Photographs courtesy of Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com, The Cleveland Plain Dealer and Zillow.com)

More...

Lizzie Borden: Warps and Wefts - 10/16/2025

[Editor’s note: Guest writer, Peter Dickson, lives in West Sussex, England and has been working with microfilm copies of The Duncan Campbell Papers from the State Library of NSW, Sydney, Australia. The following are some of his analyses of what he has discovered from reading these papers. Dickson has contributed many transcriptions to the Jamaica […]

More...